vol. 002

プロサファリガイドの加藤直邦さんが体験した、ジェーンとの逸話 Professional Safari Guide Naokuni Kato──Special Experience With Jane at Gombe

「人の心を動かすもの──それはストーリーです」

これは、ジェーン・グドール博士が常々口にする言葉。そこでジェーン・グドール・インスティテュート ジャパンは、自然環境活動や動物保護活動などに心血を注ぐ人々にスポットをあてた連載企画「Jane & Me」をスタート。「人」「動物」そして「自然」が共生する平和な世界につながっていくための“希望”を育み、“行動”へと繋げていくために、同じ想いをともにする方々のストーリーテリングを展開していきます。

第二回目は、日本人としては初めて政府公認のプロサファリガイド免許を取得した加藤直邦(かとう・なおくに)さんです。動物と自然をこよなく愛し、伝え手として野生動物の保護に尽力しています。

サファリガイドに至るまでのキャリアストーリーから、ジェーンさんとの特別で個人的なストーリーまで、ルーツ&シューツのグループの若者たちから集まった質問をベースに、インタビューを実施しました。

──加藤さんは、どんな子ども時代を過ごしていましたか?

海や山、川がたくさんある静岡県の伊豆で育ち、自然も動物も大好きでした。ヘビを捕まえて自分の服の中に入れて遊んでいたような子どもで、それを両親が怒ったりすることはなく、僕の行動を楽しんで見守り、夢をいつも応援してくれていました。

──その延長で、動物に携わる仕事がしたいと思うようになったのですね。

当時の夢は動物園かペットショップ、運がよかったらムツゴロウさんのところで働きたいと思っていたので、高校生の進路を決める際には農業高校の畜産を選択しました。でもやっぱり野生動物への情熱は消えることなく、当時はネットも発達していなかったので本をたくさん読みました。すると、野生動物が乱獲され、人間のせいで住むところがなくなり、どんどん数が減ってしまっていることを知りました。その中で、作家で冒険家のC・Wニコルさんの本と出会い、初めて「レンジャー(野生動物保護官)」という仕事があると知りました。みるみる魅了され、どうしたらレンジャーになれるのかと調べているうちに、当時日本の動物関係の専門学校がアフリカ・タンザニアにあるレンジャー育成学校のムエカ野生生物管理大学と姉妹校提携していることがわかり、専門学校で野生動物の勉強しながら英語を習得し、アルバイトで貯めたお金で26歳のときに留学しました。

──タンザニアの野生生物管理大学ではどういう勉強をするのでしょうか。

そこで自分が学んだのはワイルド・ライフ・マネージメントでした。レンジャーの仕事は、人と動物の問題を解決しながら保護区を管理していくことなので、授業は生物の基礎知識から始まり、野生動物の捕獲や調査の仕方から、密猟者を取り締まるためのライフルレクチャーまで多岐にわたります。特に印象的だったのが、「People & Protected Area」という授業です。アフリカの保護区の成り立ちというのは、植民地時代に西洋人が野生動物を狩猟したことに端を発し動物が減ってしまったため、自然を回復するために保護区を作ったのが始まりでした。ですが、元々住んでいた住民までも保護区の外に追い出してしまったため軋轢が生まれてしまい、この課題を解決するためにどうすればいいか、皆でディスカッションするというものでした。一つの答えというものはないのですが、環境教育とエコツーリズムなどについて例題をあげてみんなで話し合う時間は、非常に興味深かったです。

──そこからなぜ、レンジャーではなくガイドの仕事をしようと。

アフリカの人たちと一緒に寮生活しながら勉強しているうちに、自分たちが生まれ育ったコミュニティと野生動物を守ることに、命をかけて取り組んでいる人たちがたくさんいることを知りました。なので日本人の自分が、彼らの仕事を奪ってまでレンジャーをやる必要はないと思い、だったら自分にできることが他に何かと考えたときに、日本とアフリカを橋渡しするガイドの仕事がいいんじゃないかと。野生動物を守るという仕事は密猟者を取り締まるだけではなくて、人に伝えることもすごく大事なことです。日本にいるとやっぱり情報が少ないですから、今現地でどんなことが起こってるのかを直接伝えられる人になりたいなと思い、在学中に決意しました。ガイドは野生動物保護の一環なんです。

──日本人としては初めて政府公認のプロサファリガイド免許を取得されていました。どうしたらなれるのでしょうか?

ケニアの場合は最低でも2年以上現地の観光業に従事していないと試験を受けられません。僕はその保護区の中にあるロッジで働いていたので受けることができました。そして筆記試験は、一般的にお客さんから質問されるような「キリンの背の高さ」や「動物の平均体重」といった動物学や生態学の知識以外にも、「ケニアの初代大統領の第3夫人の名前は何ですか」といった歴史や、「首都のナイロビで一番大きな病院はどこですか」といったことも問われます。ガイドという仕事は、動物のことだけでなく、幅広い知識も必要なんだと改めて気づくことができました。

──ガイドをされていて、野生動物たちの環境はここ数十年どう変化したと感じますか。

ケニアの場合は、基本的には保護区の中にいる動物たちは守られていますが、保護区の外にいる動物はやはり住む場所がどんどんなくなっています。マサイマラ国立保護区は、元々マサイ族たちのエリアで、遊牧牧畜民といって牛やヤギの放牧をしながら、土地を転々としていました。野生動物はすべて神様のものという考え方だったので、捕まえて食べる文化もなく、今でも野生動物がいっぱいいます。しかし、資本主義的な考えが台頭し、土地という観念が生まれ、マサイの偉い人たちによって土地の再細分化が始まってしまいました。今まではみんなの土地だったのに、自分の領土みたいに線を引き始め、フェンスを作り始め、そのせいで野生動物が行き来できなくなるなどの問題が生まれています。

また、今までサバンナは季節が2種類しかなく、明確に雨季と乾季がありましたが、今は気候変動の影響で乾季でも大雨が降って洪水が起こり、極端な乾季が長く続いて動物が死んでしまうなど、ここ数十年の間に気象予測がつかなくなってしまったと感じます。

──ガイドをしていて、すごく印象に残っている出来事とはどんなことですか。

野生動物は皆が毎回違うことをしているので、常に新しい発見や驚きがあり飽きることはありません。中でも特にびっくりしたのが、ライオンとヒョウが取っ組み合いのケンカしてるのを見たことです。そういうときに限って、カメラを持っていない!(笑)マサイマラ保護区にはビッグキャットって呼ばれてる大型ネコ科が3種類いて、ライオンは草丈が高い草原を、チーターは走りやすい草原を、そしてヒョウは森や岩場など隠れやすい場所で忍者みたいな生活をしています。その棲み分けの接点でヒョウがライオンに見つかってしまい、3頭の雌ライオンに追い詰められ、激しい戦いの末ヒョウが殺されました。

──伝え手として大切にしていることとは。

今その動物がそこで何してるかっていうのを伝えられるようにしたいと思っています。そうすることによって形態や行動がわかり、その場でしか感じられない環境との密接なつながりまでもを伝えられます。例えばアフリカの動物は非常に特徴的で、模様が不思議だったり、ユニークな形態をしていたりして、サバンナという環境の中でうまく生きていくために長い年月の中で進化して今があります。食事をしているライオンの匂いや、肌で感じる日差しの強さなど、五感で感じながら知れることを最大化できるよう心がけています。

──ガイドをやってて良かったと感じる瞬間とはどんなときですか。

日本から出発してアフリカのツアーに参加するには、やはりそれなりのお金と時間が必要で、多くの人が個人的な思い入れや目的意識を持っています。なので、一人ひとりと僕はお話をし、なるべくその気持ちに応え、背中を押してあげられるようなガイドがしたいと思っています。そして感動を共有できたその瞬間、僕は非常にこの仕事の魅力を感じてます。

──ストーリーテリングの一環で、現地でボランティア活動も盛んに行われていたと。

僕はケニアのカガメガフォレストという熱帯雨林が大好きで、その好きが高じて青年海外協力隊としてカガメガフォレストで野生生物局というところに2年間所属しました。そこで環境教育を担当し、レンジャーと一緒に月に一度アウトリーチプログラムという出張授業を近隣の小学校で行っていました。電気がないので発電機とプロジェクターを持参して、森の話だけでなく僕がマサイマラで撮影したライオンやキリンの写真を見せるなどしました。すると、子どもたちはものすごい喜んでくれるんです。実は保護区にはお金も車もないと入れないため、アフリカの人たちの中にはライオンや象を見たことがない人がたくさんいます。日本だと動物園があるので見ることができますが、野生動物たちが実際に住んでいる国に暮らす人たちは動物を見たことがなく、不思議に感じました。ですから、こうして目をキラキラ輝かせながら子どもたちが話を聞いて写真をみてくれることや、将来は自分もサファリガイドになりたいと言ってくれる子どもがいたことが嬉しかったです。

他にも、カメラを持って保護区の中をウロウロしながら動物や植物を撮影し、専門家とともに種の同定をしてもらい動植物をリストアップするといった資料作りもしていました。それはビジターセンターでレンジャーや観光客が使える共有の情報源として利用できるものになりました。2年の任期を終える際にお別れパーティーをしてくれたんですけど、同僚のレンジャーだけじゃなくて、地元の人や知事、警察署長とかも来てくれて、本当にやってよかったと感じました。

──最後に、ジェーンさんと加藤さんの個人的なエピソードについて教えてください。

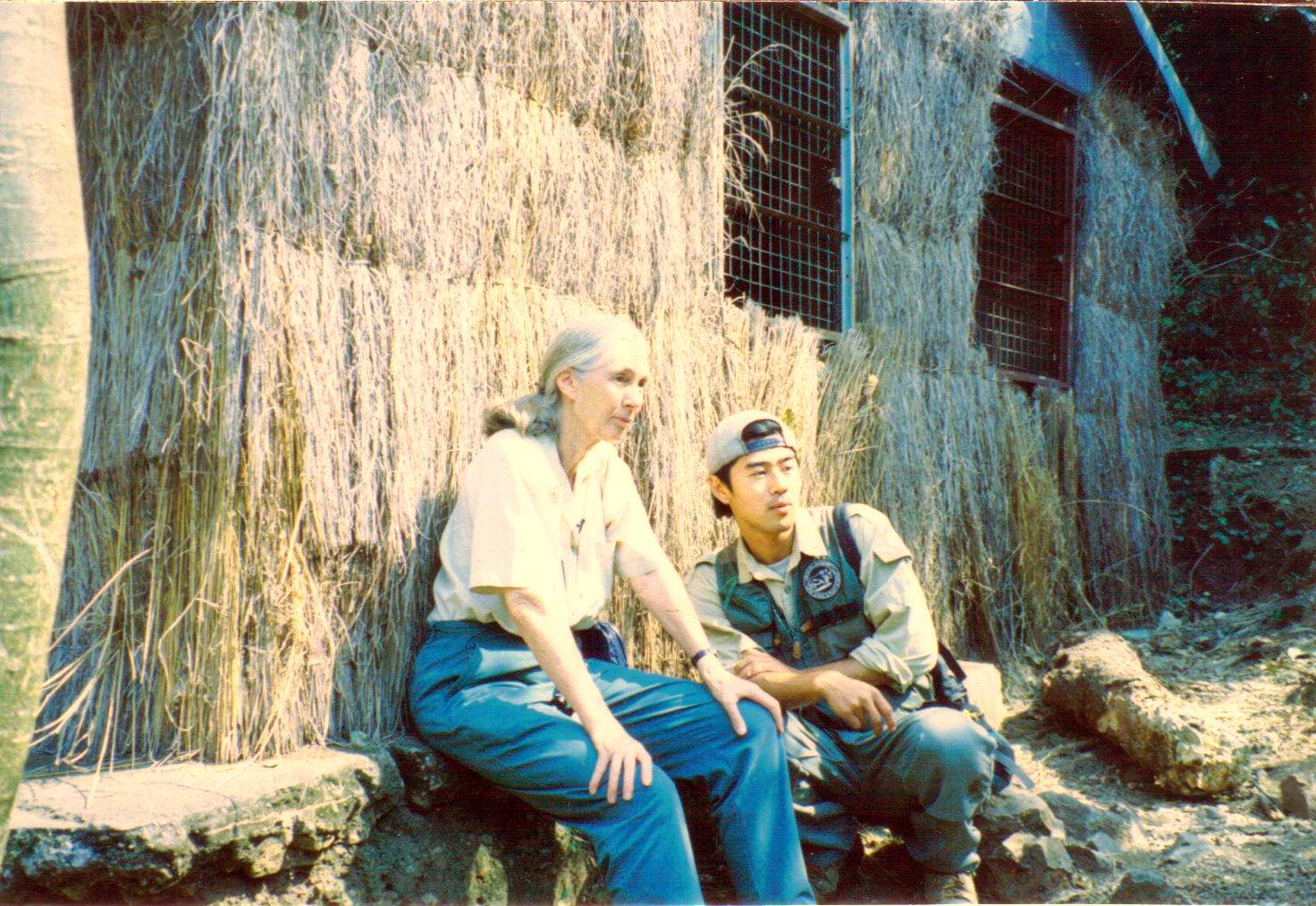

タンザニアの大学の卒業後、ガイドになるためにもっと見識見聞を深めたいと思い、保護区に帰って働いてる同級生たちを訪ねながら1年間アフリカでバックパッカーをしていました。そんな中、せっかくタンザニアにいるんだからゴンベへ行ってみようと思い、レンジャーを雇ってチンパンジーのサンクチュアリへ行きました。そこでチンパンジーを観察していたら、本当に尋常じゃないぐらいものすごいチンパンジーたちが騒ぎ出したんです。どうしたんだろう、と思っていたら、ジェーンさんが来たんです。チンパンジーたちはみんなジェーンさんと手をつなごうと大興奮。だから僕自身もチンパンジーを見たことよりも、「ジェーンさんだ!」ということでの感動が大きかったです(笑)。

そのあと、観察小屋でジェーンさんとお話しする機会があり、自分がタンザニアの大学を出て、これからは日本人旅行者のためのガイドがしたいんだという話をしたら、彼女は「それは本当にすごくいいこと」と言ってくれたのが今でも心に残っています。その言葉は、自分がガイドとしての道を歩む原動力の一つになっています。

また、そのときジェーンさんが教えてくれたのですが、今までずっと姿を消してた雌のチンパンジーがジェーンさんに会いにきて、赤ちゃんを見せてくれたそうなんです。しかもその赤ちゃんが双子だったらしく、それがすごい珍しいことだということも話してくれました。どうやったら野生動物とあれほど深く絆が作れるのだろうかと、改めて本当に驚く体験でした。

Questions by: Mori To Doubutsu

Photo: Courtesy of Kato Naokuni

Coordination: Asami Yamamoto

Interview & Text: Mina Oba

“To change someone’s attitude, you’ve got to reach their heart. I do that through storytelling”──Dr. Jane Goodall

Inspired by her words of hope, the Jane Goodall Institute Japan launched a new interview series called “Jane & Me”. We are interviewing environmental conservationists, activists, scientists, (and more!) who share Jane’s wisdom, focusing on individuals who are dedicated to building a world where humans, animals, and nature coexist in harmony.

Our second changemaking guest is Naokuni Kato, the first Japanese national to obtain a government-approved professional safari guide license in Kenya. He loves animals and nature, and is dedicated to wildlife conservation through ecotourism.

We conducted the interview based on the many questions gathered from the youth members of the Roots & Shoots group. Join us and get curious as Naokuni’s stories help us to grow our compassion and take action to build a better world.

──What was your childhood like?

I grew up in Izu, Shizuoka Prefecture, where we have oceans, mountains, and rivers. I grew up with a love for both nature and animals. I was the kind of child who would catch snakes and put them in my clothes to play. My parents never got angry with me for this, but rather seemed to enjoy watching me do what I do. They always supported my dreams.

──So that led you to working with animals.

My childhood dream was to work in a zoo, pet store, or if I was lucky, at Mutsugoro Animal Kingdom. So, in line with that dream, I chose to go to an agricultural high school and study animal husbandry. However, I couldn’t ignore my passion for wild animals and so, since the internet was not yet the incredible source of information it is now, I found myself poring over wildlife books. It was through these books that I learnt that wild animals were being over hunted and their numbers were decreasing rapidly as human behavior impacted their habitats and contributed to habitat loss. Then, I found C.W. Nichol’s book and learned for the first time about “Rangers” (wildlife protection officers). I was fascinated by their work, and while researching how I could become a ranger, I found out that there was a school in Japan that had a relationship with The College of African Wildlife Management, Mweka, a ranger training school in Tanzania. With a new dream to attend this school, I worked hard to save money, studied hard to learn English and went to Tanzania to study at the age of 26.

──What do you learn at Mweka?

My study there was focused on wildlife management. The job of a ranger is to manage nature reserves while solving problems between people and animals. The classes started by covering basic knowledge on living species, and ranged from how to capture and survey wild animals, to rifle lectures on protecting animals from illegal bushmeat trades. I was particularly impressed by the “People & Protected Areas” class. The origin of protected areas in Africa began when westerners started to hunt wild animals during the colonial period, which led to a decrease in the number of animals. Therefore, to restore nature, locals designated the area as a nature reserve. However, the people who originally lived within the boundaries of the reserve were also driven out, causing conflict. Although there is no single answer, it was very interesting to spend time together discussing the importance of environmental education and eco-tourism.

──Why did you decide to work as a guide instead of a ranger?

While living and studying in a dormitory with my classmates from Africa, I learned that there are many people who have a strong passion to protect the community in which they were born and raised, as well as its wildlife. Therefore, I thought there might be a different way that I as a Japanese person could contribute to protecting nature. I decided that as a guide I could bridge Japan and Africa by telling stories. I wanted to become someone who could tell people what is happening in the area based on my own experience . Guiding is an important part of wildlife conservation.

──You were the first Japanese national to obtain a government-approved professional safari guide license in Kenya. Could you share your story about the process of becoming a professional guide?

In Kenya, you have to have worked in the local tourism industry for at least 2 years to take the license exam. I was working at a lodge in the nature reserve so I was able to take the test. The written test not only challenges you on questions about zoology and ecology, such as “how tall is a giraffe?”, or learning the average weight of animals (questions that are commonly asked by tourists), but you are also tested on history, with questions such as “What is the name of the third wife of the first president of Kenya”, “Which is the biggest hospital in the capital, Nairobi?”…etc. I realized once again that being a guide requires a wide range of knowledge and a deep understanding of the local community, not just animals.

──As a guide, how do you feel the environment for wildlife has changed in recent decades?

In the case of Kenya, the animals inside the reserve are basically protected, but those outside the reserve are still losing their habitats. The Maasai Mara National Reserve was originally an area for the Maasai people, nomadic pastoralists who moved from land to land, grazing cattle and goats. They believed that all wild animals belonged to God, so they would not catch or eat them and valued symbiosis. As a result, the land is still full of wild animals. However, with the rise of capitalistic thinking, the idea of owning a land began to infiltrate into the Maasai way of thinking, and leaders started to divide the land. They began to put up fences, which is starting to create problems as it inhibits wild animals’ ability to come and go freely on the land.

From a climate perspective, the savanna used to have two distinct seasons – wet and dry – but now, due to climate change, even during the dry season they experience heavy rain and flooding, and animals are dying due to long periods of extreme dry weather. I feel that the weather has become unpredictable over the past few decades.

──What are some of the most memorable things that have happened to you as a guide?

Wild animals are always doing something different and show new behaviors and a different side of themselves every time we see them, so there is always something new and surprising to discover. One of the most striking moments was when I saw a lion and leopard fighting. Unfortunately, I didn’t have my camera with me at the time! In the Maasai Mara Reserve, there are three big cats. Lions live in grasslands where the grass is taller, cheetahs live where the grass is easy to run through, and leopards live like ninjas, in forests or places where there are plenty of rocks, for example, where they can easily hide. On this occasion I happened to be where these three habitats overlapped, and I watched as a leopard was spotted and then cornered by three female lions. After a fierce battle, the leopard was killed.

──What do you value the most when you guide?

My priority is sharing what the animals are doing right here, right now. By doing so, we can understand their forms and behaviors, and even convey a close connection with the environment that can normally only be felt at that place. For example, African animals are very distinctive, with very unique patterns and forms, and have evolved over many years to survive in the savanna. I try to maximize what we can learn by feeling with all five senses, such as the smell of a lion eating or the intensity of sunlight on the skin.

──What do you find most rewarding about being a safari guide?

Participating in a tour of Africa from Japan still requires a fair amount of money and time, and people who do make it tend to have their own desires and sense of purpose. So I make an effort to talk with each person and understand those desires so they can spend their time in a way that best suits them. One of the most fulfilling moments for me as a guide is when we share a moment of awe and excitement.

──Continuing on the theme of storytelling, could you also share about your volunteer work?

I love the tropical rainforest called Kakamega Forest in Kenya, and my love for it led me to join the Japan Overseas Cooperation Volunteers (JOCV), where I worked for two years in the Kakamega Forest in the Wildlife Department. I was in charge of environmental education there, and together with a ranger, I conducted a monthly outreach program at local elementary schools. Since there was no electricity, I took a generator and projector so I could share stories about forest conservation. What surprised me was how excited the children became when I started to show photos of lions and giraffes I had taken in the Maasai Mara. It turned out that, since you need both money and a car to enter a nature reserve, there are many people in Africa who have never seen a lion or elephant in their life! In Japan, you can see them in zoos, but people living in countries where these wild animals actually live in their natural habitats have often never seen them, which I found very strange. So I was happy to see children listening to our stories and looking at the photos with their eyes glistening, and especially to hear some of them say that they would like to become safari guides in the future.

I also worked on other projects, taking pictures of animals and plants in the reserve, and working with experts to identify species to make a list. This list evolved into a shared source of information available for use by rangers and tourists at the visitor center. At the end of my two-year term, they held a farewell party for me. Not only my fellow rangers but also locals, the governor, and even the chief of police joined us.I felt very grateful and proud of my work.

──Final question, please tell us about your personal episode with Dr. Jane.

After graduating Mweka (the college in Tanzania), I wanted to deepen my knowledge and experience to become a guide, so I went backpacking in Africa for a year, visiting classmates who had returned to work in nature reserves. During this time, I decided to go to Gombe where the Jane Goodall Institute has their largest chimpanzee sanctuary. While I was observing the chimpanzees there, they suddenly got excited and started to make an unusual and tremendous noise. I wondered what was going on, and then I saw Jane coming. All the chimpanzees were clearly very excited. Apparently they all wanted to hold her hand! So I also found myself more moved by the fact that I had met Dr. Jane than the chimpanzees…!

After that, I had a chance to talk with Dr. Jane at the observation hut. I told her that I had graduated Mweka and wanted to become a guide for Japanese travelers. She said, “That is such a wonderful choice you made,” which still remains in my heart. Those words have been one of the driving forces for me to follow my own path as a guide.

At the same time, Dr. Jane also told me that a female chimp that had been missing for a long time came to see her. The chimp showed her her twin babies, even more incredible given that twins are incredibly rare. It was a truly amazing experience that made me wonder how she builds such a deep bond with wild animals.

Questions by: Mori To Doubutsu

Photo: Courtesy of Kato Naokuni

Coordination: Asami Yamamoto

Interview & Text: Mina Oba

Editor: Mariko McTier